"Hog outlook bright despite tough time"

The headline blaring from the page in a recent Manitoba Co-operator

would have been funny if the topic wasn't so serious. It could also have

been accompanied by a couple other adages like "It's always darkest

before the dawn" or "It's better to light a single candle than to curse

the darkness". If a person had a nickel for every prediction that good

times were just around the corner for the hog industry, you could

probably buy a hog barn and fill it with stock.

Actually, the barn might cost you something, but the stock could likely

be had for free. Another farm paper, the Western Producer, carried a

story the same week about the inability of farmers to get anything at

all for cull sows and boars. One Alberta hog farmer was told he would

have to pay four cents a pound to get someone to take his cull sows.

All this is occurring because there is an oversupply of pork, a

non-competitive processing industry, high feed grain prices and so on.

The problem is similar in the cattle industry. Canada's current cowherd

was built on the prospect of free trade and the reality of a low

Canadian dollar. Unfortunately, a high Canadian dollar pretty much nixes

the benefits of free trade, which hasn't been all that free lately

anywayy. Some analysts predict that with grain prices likely to remain

high for some years, the Canadian cattle herd will shrink back to a size

that fits the domestic market.

It is, after all, about supply and demand. If there is no demand for

beef at higher prices, and today's prices make a farm unsustainable,

farmers will leave the industry, supply will decline and prices will

rise correspondingly. No one really doubts that this will occur in the

beef industry. That it isn't happening yet in a significant way probably

reflects the fact that farmers usually hang on a year or two after the

market tells them to get out. It's like you can't believe the family dog

bit you until he does it again.

So in the free market, the same thing should happen to the hog industry.

Right? But hogs have been an unrelenting disaster in Canada for years

now, sustained only by repeated government bailouts to the industry.

Short of bankruptcy, which did take down quite a few barns in western

Canada in recent years, hog producers remain stubbornly productive. The

once-reliable four year hog cycle has been stuck on permanent press now

for quite a while. Despite this, producers have failed to be squeezed

out, as markets would say they should. Now, we even have a government

program paying farmers to kill their sows and boars, in an effort to

force the downsizing that obstinately hasn't occurred.

There is a simple reason for the failure of economic theory here, and it

is centred in the factory hog farm. When hogs were produced on thousands

of family farms, dozens here, hundreds there, farmers easily shifted in

and out of production as prices dictated, thus setting up the

predictable cycle.

Large hog farms cannot afford to do this, considering the huge amounts

of capital they have tied up. They must produce, even if the margins are

zero. Things have to become excruciatingly bad for the big guys to

leave. With all the small producers gone, the market cycle just doesn't

work.

Cattle respond to a longer cycle, more like ten years. With thousands of

cow-calf producers, the cycle will assert itself. With high grain

prices, ageing farmers, and paltry returns, many will leave the

business, never to return. But look at what is happening to the cow-calf

industry. Economics dictate that herds today must be huge to produce any

kind of return. While the average herd is still around 60 cows, there

are increasing numbers of farmers running 400, 500 or 1,000 cows. And

these folks are not mixed farmers. That many cows don't leave a lot of

time to grow grain.

There are some parallels to the hog industry here. Cattle producers of

this size are not reducing herds in response to low prices. Many are, in

fact, expanding, taking advantage of fire-sale cow prices.

Given this, will the cow cycle begin to break down, as it has for hogs?

Will we eventually see the government paying farmers to shoot cows and

dump them for the coyotes in order to get the price back up? I figure

that day will come right around the time we start to see headlines

predicting a rosy future for the cattle industry just around the corner.

(c) Paul Beingessner Column # 662

Sunday, March 30, 2008

Farmers Guess Badly on Wheat Sales 22/10/07

Western Canadian Wheat Grower vice-president Stephen Vandervalk is no

quitter. Despite showing the world how wrong he was he isn't giving up

on his diatribe against the Canadian Wheat Board.

In August, the feisty Albertan ranted against the CWB's Pool Return

Outlook (PRO) for barley. He trumpeted his own cleverness at selling

much of his yet-unharvested crop before the CWB announced it would

challenge the federal government's attempt to remove the single desk

from malt barley and exports of feed barley. That challenge, according

to Vandervalk, caused the price of feed barley to plummet and cost him

big bucks on his remaining unsold stocks. As to malt barley, Vandervalk

said a maltster offered him $4.75 a bushel for his. The court case put a

stop to that and he claimed the lower price the CWB was projecting would

cost him dearly.

A short month later, Vandervalk should have been gnashing his teeth. The

September PRO was projecting $5.43 for malt barley at his Alberta home

and the feed barley he pre-sold for $4 was projected to be worth $4.64

delivered to the CWB. Vandervalk lost big all right, not because of the

CWB, but because of his own feed barley marketing folly. The CWB court

case saved his from making the same mistake with his malt barley.

Rather than be chastened by his marketing failure, Vandervalk continued

on his quest to damn the CWB. In late September, he was showering farm

newspapers with information comparing U.S. elevator prices to the CWB

PRO. According to these figures, Vandervalk was losing a small fortune

because he could not sell his durum across the line. Comparing the

elevator price in Montana, which hit $13.10 a bushel that week to the

CWB PRO of $10.70, Vandervalk's estimated deficit would be $151,000.

You have to give Vandervalk some credit here. Despite being prevented

from ever marketing his own durum by the CWB monopoly, he apparently

would be far better at it than most American farmers who do it all the

time. According to the marketing director of the North Dakota Wheat

Commission, most durum farmers in his state missed out on the high durum

prices because they sold earlier, at much lower prices. Those prices

looked good at the time and no one was projecting the heights to which

durum would soar. Nor were North Dakota farmers the only poor marketers.

Wheat farmers in Washington state also blew it, selling some 70% of

their crop before prices reached their highs. As much as 50% was sold at

values roughly half those available today.

If Vandervalk were selling his own durum, it seems safe to assume he

would have done what he did with his feed barley - sell much of it early

for what appeared to be good prices. It is unlikely he would have had

enough foresight to wait until the day it hit $13 at a Montana elevator.

It is also unlikely any Montana elevator would have been able to absorb

his reported 63,000 bushels in one fell swoop.

Luckily, and despite his efforts to the contrary, Vandervalk has the CWB

to protect him from his misadventures. No, the CWB will likely not sell

all of western Canada's 4 or 5 million tonnes of durum at $13.00 a

bushel. The U.S. can absorb only a small amount of our durum. The rest

will be sold over the course of the crop year for various prices to

various countries. And it will incur some large rail and ocean freight

bills. But this year, the CWB will likely return far more to durum

farmers in western Canada than their American brothers will receive,

since much of their durum has already been sold for a relatively low

price. Stephen Vandervalk is one of those lucky Canadian farmers, and if

he were honest with himself, he would admit it.

(c) Paul Beingessner Column # 642

quitter. Despite showing the world how wrong he was he isn't giving up

on his diatribe against the Canadian Wheat Board.

In August, the feisty Albertan ranted against the CWB's Pool Return

Outlook (PRO) for barley. He trumpeted his own cleverness at selling

much of his yet-unharvested crop before the CWB announced it would

challenge the federal government's attempt to remove the single desk

from malt barley and exports of feed barley. That challenge, according

to Vandervalk, caused the price of feed barley to plummet and cost him

big bucks on his remaining unsold stocks. As to malt barley, Vandervalk

said a maltster offered him $4.75 a bushel for his. The court case put a

stop to that and he claimed the lower price the CWB was projecting would

cost him dearly.

A short month later, Vandervalk should have been gnashing his teeth. The

September PRO was projecting $5.43 for malt barley at his Alberta home

and the feed barley he pre-sold for $4 was projected to be worth $4.64

delivered to the CWB. Vandervalk lost big all right, not because of the

CWB, but because of his own feed barley marketing folly. The CWB court

case saved his from making the same mistake with his malt barley.

Rather than be chastened by his marketing failure, Vandervalk continued

on his quest to damn the CWB. In late September, he was showering farm

newspapers with information comparing U.S. elevator prices to the CWB

PRO. According to these figures, Vandervalk was losing a small fortune

because he could not sell his durum across the line. Comparing the

elevator price in Montana, which hit $13.10 a bushel that week to the

CWB PRO of $10.70, Vandervalk's estimated deficit would be $151,000.

You have to give Vandervalk some credit here. Despite being prevented

from ever marketing his own durum by the CWB monopoly, he apparently

would be far better at it than most American farmers who do it all the

time. According to the marketing director of the North Dakota Wheat

Commission, most durum farmers in his state missed out on the high durum

prices because they sold earlier, at much lower prices. Those prices

looked good at the time and no one was projecting the heights to which

durum would soar. Nor were North Dakota farmers the only poor marketers.

Wheat farmers in Washington state also blew it, selling some 70% of

their crop before prices reached their highs. As much as 50% was sold at

values roughly half those available today.

If Vandervalk were selling his own durum, it seems safe to assume he

would have done what he did with his feed barley - sell much of it early

for what appeared to be good prices. It is unlikely he would have had

enough foresight to wait until the day it hit $13 at a Montana elevator.

It is also unlikely any Montana elevator would have been able to absorb

his reported 63,000 bushels in one fell swoop.

Luckily, and despite his efforts to the contrary, Vandervalk has the CWB

to protect him from his misadventures. No, the CWB will likely not sell

all of western Canada's 4 or 5 million tonnes of durum at $13.00 a

bushel. The U.S. can absorb only a small amount of our durum. The rest

will be sold over the course of the crop year for various prices to

various countries. And it will incur some large rail and ocean freight

bills. But this year, the CWB will likely return far more to durum

farmers in western Canada than their American brothers will receive,

since much of their durum has already been sold for a relatively low

price. Stephen Vandervalk is one of those lucky Canadian farmers, and if

he were honest with himself, he would admit it.

(c) Paul Beingessner Column # 642

Friday, March 21, 2008

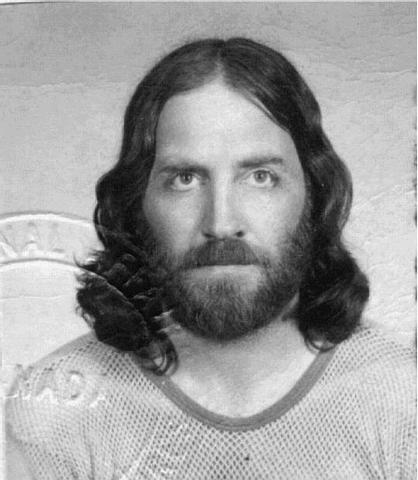

Paul Beingessner

Paul Beingessner is a farmer and journalist from Saskatchewan whom I greatly admire. His knowledgeable articles on rural issues appear in many small-town papers across the prairies as well as in farm journals. He scathes the politicians and corporations who escape the scrutiny of most of the city-based media, even though the issues do also affect urban people in food prices and the countries economy.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)